Spotlight: The South Providence People's Archive | feat. Cheryl Monroe

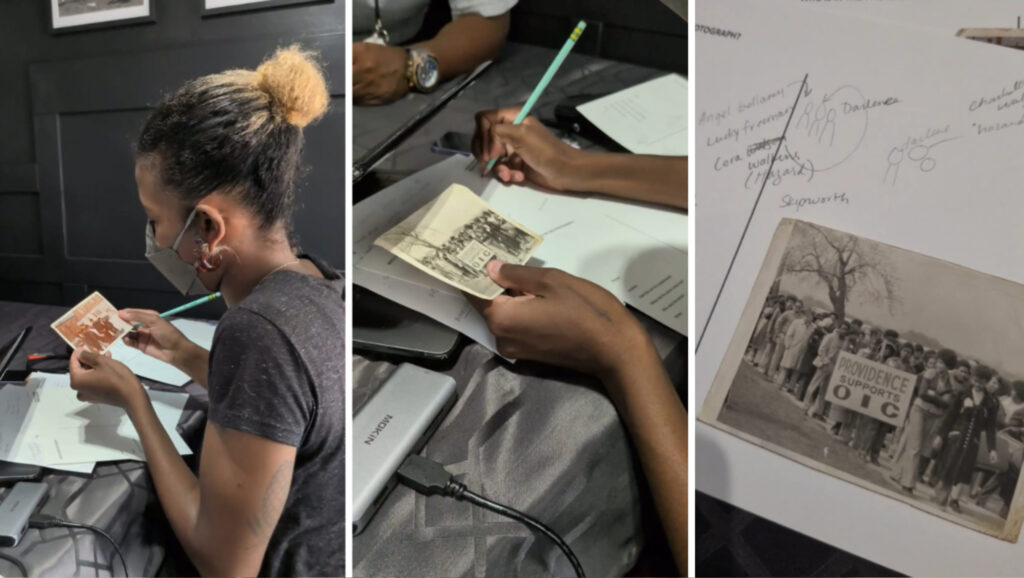

For this spotlight feature, we did something a little different. We went “on location” with the South Providence People’s Archive (SPPA) led by PCL artists Edwige Charlot and k. funmilayo aileru and visited the home of Providence resident Cheryl Monroe. We got an up close look at SPPA’s one-on-one archiving session where they gather and record stories from residents, creating a multimedia archive of the lives of the South Providence community. Read some vignettes from Cheryl’s story and get a glimpse of the archiving in action.

To start, tell us a little about the SPPA.

funmi: The South Providence People’s Archive — we like to call ourselves an emerging collection, both digitally and physically, of materials pertaining to Black and Indigenous people, community, and culture on the South Side. And more specifically, we’re concerned with intimate life and depictions, and how these accounts continue to expand the public record. In local archives and other historical repositories, a gap that we continue to notice is that, at least with state and city-sanctioned archival materials, they tend to focus on the physical place, the architectural infrastructure of a place that is often, unfortunately, devoid of people. In shaping our project, [we wanted it to be] in relationship to conversations with various community members, grassroots and community-based organizations, around how folks would like this place and its people to be commemorated. Our initial conception was along the lines of a memory and dream book, but over the last year, that has evolved into a more extensive people’s archive.

Edwige: When we identified Black and Indigenous stories as our framework, we were thinking about those identities pretty extensively. I think Rhode Island has this intersection of both Blackness and indigeneity that is very specific to this region. We’re thinking about Caribbean folks, Afro-Latino folks, recent migrants and immigrants, recent transplants to the city… This is where the ‘dream’ part [of the project] was really being held, and the memory component was really trying to ensure that the collective memory was a part of those institutional archives. Being able to footnote, to highlight, to clarify, to correct, and to provide lived experiences through those first-hand accounts has been an important part of our archive development and will drive how the archive continues to develop, because it is people-centered and people-driven. This is a stewardship project, and that is how we frame this practice of commemoration and remembrance.

How does the community typically participate in this archiving?

Edwige: funmi and I started, fairly early on, by designing our own ways of being and engaging in this process. We were contending with how we saw institutions, entities and organizations facilitate their own archiving work. We thought about how we were handling collections, we thought about access. Many, if not all, of these institutions that hold public collections, are accessible to the public. However, these sites are often not welcoming. There are many barriers to accessing them, and so we were really thinking about how we wanted to engage with folks. Trust building was a large component: how we were meeting with them, how we were making asks, how we were laying out informed consent throughout our process and giving people opportunities to say “No, thank you” at every juncture. For me, it was about being a proper guest, and understanding my role as a steward. The ways that our engagement showed up looked like a lot of deep listening, researching, providing access to things that I found, that I continue to find, making connections, making introductions, meeting people exactly where they were at, whether it was on foot, by car, in public spaces, in their home museums… It really started with our own framework as stewards, and then as artists. And folks understanding that was also part of the repair process. We also had to atone for a lot of the extraction that has happened on the South Side over many years, especially around arts and culture.

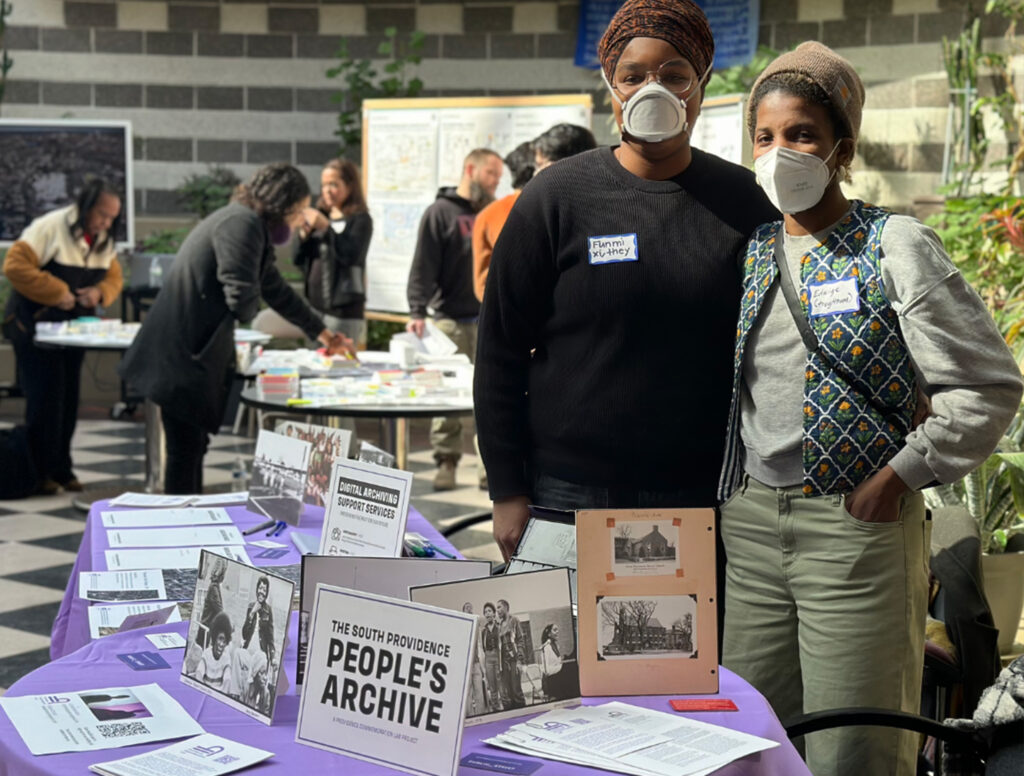

funmi: Our entire process is relationship-based. When we are engaging folks, whether it be tabling at an event and introducing ourselves, or when we’ve had opportunities to join city meetings, neighborhood associations or different settings where people are gathering… It’s about not just coming in off the top and expecting something from the folks that we’re engaging with, but really practicing a principle of reciprocity. With various touchpoints like [archiving] pop-ups throughout the South Side, tabling at community events, or doing one-on-one appointments — many of those have come out of intimate relationship building and a process of… validation. Folks are gonna wanna know who you are, who your people are, and what your relationship is to this space. It’s been a plus that my family is from the South Side. Growing up on Prairie Avenue very close to the Public Street intersection, and Edwige’s very intentional and slow process of getting to know people… it lets folks know that we’re trustworthy and builds safe enough conditions where they feel okay to have a conversation about their history, their family’s history, or the culture of the Southside. People are entrusting us with their families’ materials.

On that note, give us a little background on who Cheryl is before we get a glimpse at her archive.

funmi: Yeah, so full disclosure, Cheryl Monroe is my aunt. My mother and Cheryl are sisters. She’s always been a pillar within my family and within my community. Everybody knows Auntie Cheryl. Auntie Cheryl will give you the shirt off her back. She’s involved with many things having to do with the South Side. If you have an event, or you need support with something, Auntie Cheryl is always the person to do that, whether it’s promoting what you’ve got going on, trying to help you start something… that’s just the person she is, both in my family and in our wider South Side community. She’s also an author and a disability advocate, a spiritual aid person — there’s many facets to Auntie Cheryl. And we thought that she would be an ideal person who embodies the values and culture of South Providence. It’s also a process of honoring our elders. There’s a saying about learning at the feet of your elders. Auntie Cheryl is someone I consider to be one of those people.

Vignettes from the Archive

“And we painted the car. With spray paint!”

From the archive of the Monroe family, recorded 27 August 2025

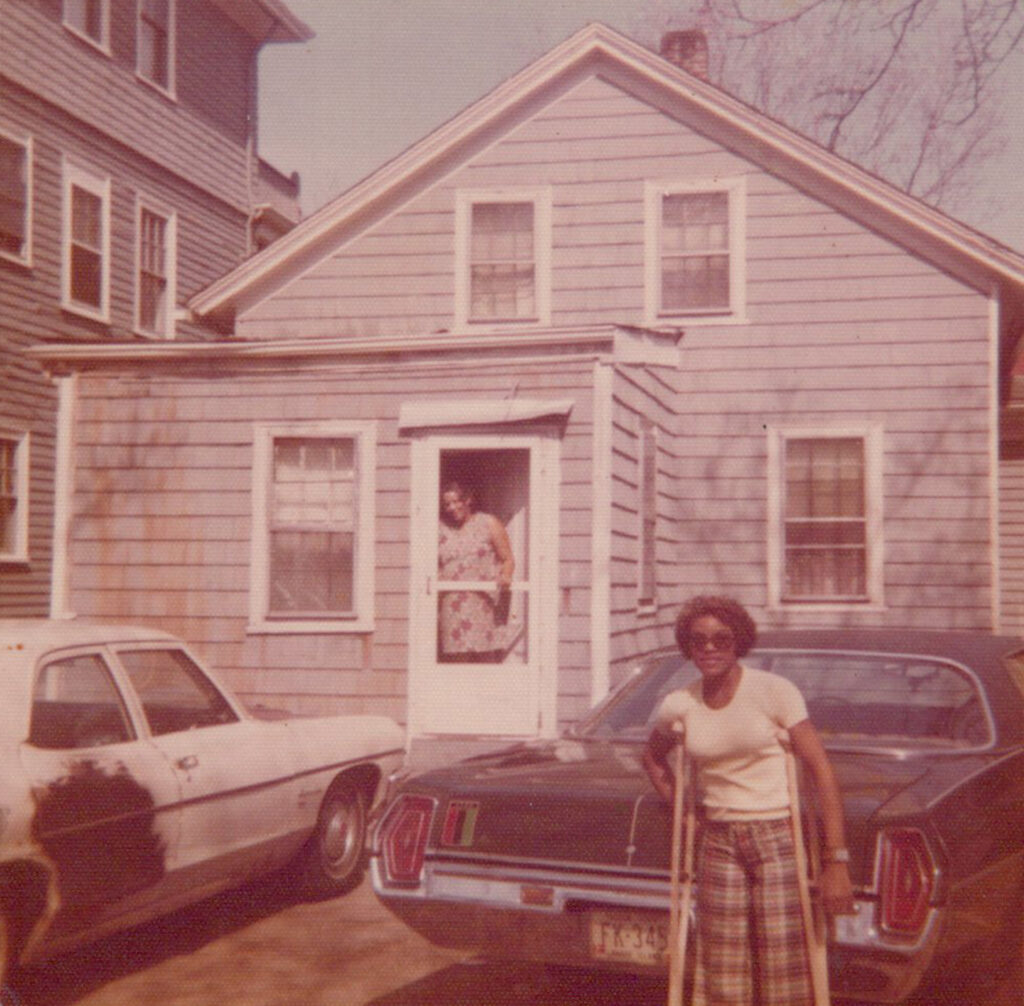

Cheryl: This house, sheesh … This house had many memories. I mean, we were there forever and forever. I was so cute back then. [laughs] I’m kidding!

Edwige: No, you were!

funmi: You were!

Edwige: You were so cute.

Cheryl: [laughs] The house wasn’t luxurious inside, but it had a lot of character. It had a lot of personalities inside. Upstairs where the two windows are … one was my bedroom window, and me and my sister Sissy shared that room. The other window was the TV room, and we spent a lot of time in the TV room. The window over this side was the dining room and the window over that side was the kitchen. And actually, the side where the kitchen was, my two brothers, Mingo and Allen, built a deck out there in the back. And I’d go up there late at night and just sit. Just sit out there and have a cup of coffee. I did a lot of coffee back then … I think that’s what stunted my growth. [laughs] My grandmother would always say, “If you drink too much coffee, it’s gonna stunt your growth, and coffee makes you nag, nag, nag, nag, nag.” There were a lot of memories in that house. I mean, my mother took in many people. Every time my father came home, he would have a new truck driver with him, every single time. My mother would put them up, give them a blanket, let them sleep on the couch … And she complained about it, but I think at the same time she liked it, because she’d always say, “Would you like a cup of coffee? Would you like something to eat?” And of course, they always said yes. But she complained to my father all the time, “You’re always bringing home strangers.” But I think in her heart, she enjoyed the strangers. My mother didn’t mind feeding, she didn’t mind helping, she didn’t mind taking in, she didn’t mind any of those things. So I think that was her way of showing that kind of love. And that white car right there, that was my father’s car. And that big black spot on the side was because I believe he let Darlene and Gail use it when they went out partying or something, and I think they got in an accident with it. And my father ended up doing a lot of detail on it, he was self-taught, and that’s what that black spot was. He got a dent-puller, pulled out all the dents, and then sanded it down, put the putty up in there, and did what he did. And we painted the car. With spray paint! [laughs]

funmi: I know that’s right.

Cheryl: Yeah, so he was very self-sufficient when it came to things like that. We didn’t have a lot of money. You know, you got what was put before you. Sometimes siblings don’t like to talk about those hard times, but those hard times are what shaped you. So I don’t mind telling people, I really don’t. My parents had nine kids. But [despite] having nine kids, we never went without. We never went without Christmas. We never went without clean clothes. We never went without Easter clothes. And on Easter, my mother always got two outfits for us: one to wear to church, and one to change when you came home. So they made it work with the little they had. That’s what made it rich.

“There were no grades.”

From the archive of the Monroe family, recorded 27 August 2025

Cheryl: I didn’t start school until I was like seven years old. The school I went to was called Mary C Greene. And are you familiar with that?

funmi: Mary C Greene…? Yeah, no.

Cheryl: It used to be called Mary C Greene, but now it’s no longer that. It’s off of Broadway… I forgot the name of the school, but only one section of it was called Mary C Greene, because that was the school for people with disabilities. And so they took a section of it, a very small section of it. And then after that, I went to Smith Street School. That was a horrible experience. I was the only girl in the whole school with a physical disability, and so there was a lot of bullying, you know … Taking my crutches from me, trying to coerce me to get my ice cream money. I gave it to him. Because I wanted my crutches back. [laughs] But then after that, I told my teacher about it, and she kind of dug into him. So that made my last year there a little bearable. Then I went to Nathan Bishop, I went there for one year. And that wasn’t a good experience. I got bullied a lot. It wasn’t because of who I was, it was because they saw a physical disability. That’s why they did what they did. And it’s funny, because when I run into some of them, and I remind them of that, they’ll say, “Hey Cheryl, you look so good. What are you doing?” And I’d say, “Oh, yeah, you remember you used to bully me?” And they’d say, “I never did that.” And I’d say, “No, you did.” And I remind them exactly what they did, and they don’t know how to receive it. They’d say, “If I did that, I don’t remember.” And I know, sometimes we have blocked memory, or whatever you want to call it. You’re suppressing it. And that’s fine. That’s okay. But you know what? I don’t have a problem with it. We’re mature now… [Anyway] so there [at that school], I was kind of wondering, why are we in the basement? Everybody else is up on the other floors. Well, back then they put the kids that had disabilities in the basement. Because God forbid if someone walks in the front door and sees kids that are different from their kids, you know? So they were always put in the basement. And there were no grades. And I asked my teacher, “What grade is this?” And she said, “Oh, no, we don’t have a grade.” “There’s no grade? How do you grade us?” And she said, “Well, this is pretty much the ungraded pool.” And so you pretty much just get like a letter by your name … it was more like a promotional kind of passing. But what happened was, I was put into a pool, and I was able to get into inclusion. So my first experience being in a regular classroom was my first year at Roger Williams Middle School. And my last two years there were good experiences. I got to meet some good friends. They didn’t only see the disability, they saw me as a person. I gained close friends from that time, and they always wanted to help out. And, you know, I got to go down the teachers’ staircase because the hallways were crowded. I got to leave the classroom five minutes early. So my junior year at Roger Williams, that was a good experience for me. That’s when I began to really gain confidence in myself, that I could be, you know, normal … When I graduated from there, it was crazy because I was saying to myself, “How am I gonna get up on that stage?” Because there’s no handles or nothing, you know? And so I’m like, “How am I gonna get up ‘em stairs?” But I got up ‘em, and it’s crazy because they actually gave me a standing ovation. I was the only girl in that school with a physical disability.

What are the kinds of stories and patterns you see emerging from the archive as it grows?

Edwige: From what I’ve experienced one-on-one with how people recount their lived experience, and what the state-sanctioned record reflects, there’s a lot of dissonance in what is recorded and what people have experienced and lived through. Everything that we shared has to be understood through that framework; that is the mesh that is overlaid on people’s experience. And I think we can’t talk about the themes of thriving, abundance, joy, culture creation and placekeeping that we see through the People’s Archive without talking about the historical context and conditions in which people were experiencing them. The South Side is a microcosm for larger societal issues and ailments. But there’s much to learn from the way that people have persisted. So creativity and imagination are two words that [come up]. There’s so much ingenuity in how people have persisted, and the biggest thing that I’m walking away with is a better understanding of the level of cultural production that happened on the South Side that is unknown to the city — street photographers, talented musicians… just because people were not featured in the newspaper getting awards, it didn’t mean that it wasn’t happening, right? The only time that folks are mentioned in the record are when they’re being counted to serve as data to justify a decision that they’re being told is happening to them.

funmi: I think what emerged for me over time is how I now consider the South Side, where I was born and raised, very much a constellation. Even folks who might not be in direct connection or relationship with one another, there are still other ways that they may have missed each other, or been in proximity to each other, and just didn’t know each other. Finding out the ways in which people are directly and indirectly related continues to highlight the close-knittedness of the South Side. It’s just a refreshed way of looking at the space, even now as it’s rapidly changing. We’ve had gentrification, we’ve had redistricting. Especially for my generation — the millennial generation — many of us do not physically live there anymore. However, with this, we still maintain a deep connection. We often work there, we’re constantly over there for one reason or another. Even a community member we were working with this past weekend remarked how grounded they were in the space that we were doing a photo shoot in. I continue to feel that too. That feeling seems to remain consistent throughout the generations. We could focus on things like the constant leveling of houses, the clearing of community spaces, the clearing of schools, the installation of parking lots… but that said, there is an enduring connection of a people to a place that is very robust.

“My first trip to New York…we went to see The Wiz.”

From the archive of the Monroe family, recorded 27 August 2025

Cheryl: When we lived on Comstock Ave… I don’t know if any of you have ever heard of Chester “Buddy” George? He was kind of like the father of Southside. He used to load us up on his bus, he came around to each house, knocking on the door, getting your mom’s permission to sign you up. He signed you up, and he’d take you just all over the place. My first time, we went to Rocky Point. Every weekend, they just came to do something amazing for the kids in the community. My first trip to New York was with him on the bus. It was me, my sister Darlene, my sister Gail, and we went to go see The Wiz.

funmi: Yeah, my mom’s told me about that.

Cheryl: Yeah. See? So I’m telling the truth, right? [laughs]

funmi: Yeah, yeah, I can verify that from what I know.

Cheryl: Yeah, so we went to see The Wiz, and it was amazing. It was amazing. That was my first actual play that I’d seen that was pretty much predominantly black. And so that was a good experience. I love plays, musicals, that’s me, I just love all that stuff. And Buddy George also had… it was called the Drop-in Center, and you could go every Saturday. They’d have hot dogs and juice and chips for the kids every Saturday. And that was a place you could go. It was like a little rec. That was a place where you could go, and your kids would never be in trouble. He always made sure that there was something for the youth to do. That’s just the way he was. He always tried to keep the young men out of prison, and when they came out of prison, they’d connect with him right away to help them get back on the right track. Some didn’t, and some did, you know. And he was just a really… he just set a great example, as a man for the community.

“Don’t be somebody else’s dream killer.”

From the archive of the Monroe family, recorded 27 August 2025

Cheryl: I graduated from Central and I was setting up for college and things. Ma would not let me go on campus. She was like, “No, because, you know, the world’s crazy.” The world’s crazy today, if she only knew! [laughs] She let me branch out, but she was also over-protective at the same time. She never said it, but I guess her biggest thing was — you’re disabled, you know, you can’t easily defend yourself. So it was a definite no for campus stay. But the gentleman came to the house to help fill out the FAFSA. We got halfway through the paperwork. My mom and dad were sitting at the table, and he looks up at my dad, and he says, “You know, Mr. Monroe, I don’t think that Cheryl is college material.” And my father says, “What do you mean, she’s not college material?” He said, “Well, you know, I just don’t think she’s meant to cut it.” My father looked at me, and he was like, “No disrespect to you, but you know what, you can leave.” So he went to walk out the door, but he said, “Well, I need to help her finish the paperwork.” But my father was very self taught, so he said, “No, that’s okay, we’ll get it done.” And my father escorted him out the door. And before he left, my father said, “Oh, and by the way, don’t be somebody else’s dream killer.” And you know, like, wow. My father always stood up for me, and lo and behold, I ended up going to college.

“We had this thing with sunflowers, we made sunflower pillows…”

From the archive of the Monroe family, recorded 27 August 2025

Cheryl: There was a neighbor who lived across the street on Comstock Ave. And I became good friends with her. Every other weekend I’d spend at her house. My mother used to say, “You’re gonna wear your welcome out.” But we ended up being best friends. My father was a truck driver, so he always brought extra stuff home from the rig. He’d bring watermelons, apples… So he’d set up a stand outside, and some of my siblings would do it, but after like an hour or two, they’d say, “I’m done. I’m not doing this.” But I’d be out there till the sun goes down, selling the last apple, orange, watermelon, whatever it was my dad had. Those are just the things in your community that shape you, because you see other people driving and just pushing through, so you’re like, wow, maybe I can do that, you know? Me and my sister Darlene, we used to always make little pillows out of burlap and stuff them. We took sewing classes, she liked to sew. We did a lot of things by hand, because my mother always sewed by hand, and she taught us how to backstitch by hand so that things wouldn’t come apart. We used to make burlap pillows. We had this thing with sunflowers, I don’t know why. [laughs] But we made sunflower pillows and we stuffed them and we walked through the community selling them. We’re selling like $2 apiece or a dollar apiece, or 75 cents or whatever. And people would buy them. [So we’d say] let’s go make some more. Things like that, just being part of that community helps shape you. It helps you be strategic. It helps to use critical thinking. How’re you going to map this out, you know?

Edwige: It sounds like you had an entrepreneurial spirit from the beginning, right? You were just resourceful, and the community gave you opportunities to showcase that, right? And you were received.

Cheryl: Yeah, that was the good thing about it. The community didn’t look at us and just see these sisters, these two girls. They [just] bought the pillows or the candy or whatever it was we were selling. So that too is a part of shaping you, you know? Being welcome is… it’s important. It’s important to be seen.

“My norm is not your norm.”

From the archive of the Monroe family, recorded 27 August 2025

Cheryl: My first book, I named See Me Not My Disability. Because I’m not my disability. And to this day, it’s still a struggle. To this day, it doesn’t bother me like it once did, but it just behooves me more than ever … why are we still trying to make way for people with disabilities? Why are we still trying to make access to certain buildings where you can’t get in? Why are we still trying? Why are we still trying to make people with disabilities and wheelchairs and scooters fit into bathrooms they can’t fit in? I don’t know, it’s crazy, you think that the world would have gotten better.

Edwige: In the research that funmi and I did, we were just looking at the trend of fresh air schools and… you know… It’s hard, I have to say. I mean, you lived it, but it’s hard to hear about you being the one and only, right? And you not having that sense of belonging until your later years? Because you were hidden, you were in the basement, you were treated very differently, and you didn’t have access. But it sounds like the neighborhood treated you differently from the way the system did.

Cheryl: Yes, absolutely. That’s another thing my father always said: “Only you know your limits, and so never let society tell you what you can and cannot do, because only you know. The only one that can limit you is you.” And he said, “I don’t see you as handicapped, I see you as handicapable.” And so I always carry that with me. In everything I do, I always make sure I include that quote, because that’s what’s always kept me going. And look at me, I am a person, you know, and I deserve everything everybody else does. I deserve it too. I deserve to live a “normal” life. But people look at that word “normal”, and I’m like, what is normal? My norm is not your norm. Okay? My normal is getting up off my bed, scooting on my scooter. That’s not your normal, because you don’t have a scooter, you don’t have to scoot. People have really taken that word “normal” out of … [they say] “Oh, that’s not normal.” Well, why isn’t it? That’s my normal.

What is your hope for this project? What do you envision for the future of this archive?

funmi: The hope is that it continues. I want to acknowledge that there are other organizations and groups that continue to do archival work around Black American life in Providence, some of which may or may not be specific to South Providence. So, number one, wanting to acknowledge and name that. But number two, what I’m looking forward to and excited about is the People’s Archive being an interpersonal place where folks can record themselves but also connect to other people. A place of connection and also a space to record our own stories, beyond just birth, death, marriage, court records… And also not needing to have a legitimizing institution to do that. So that folks can make that choice to opt out if they want to. I hope that folks are able to contribute accounts of their life on their own terms, and that the archive can be a vehicle for that — a community-determined space for archival work.

Edwige: The biggest wish that I have for this project is for it to continue to be stewarded by a group of people, and for it to evolve as the community and the collective sees fit. Both on a personal level and a collective level, I would be happy to see others do this work. And I hope that the People’s Archive can become a place for people to learn that the ways in which they engage with their own lives is an archiving process, right? The ephemera around us — our planners, our notes, our school pictures, our names and programs — all those things that exist in the physical world are important. They have a life that is worth sharing. My hope is that this type of work can be a space where arts, culture and humanities intersect, in a way that continues to be supported and valued by our society and our community.

The South Providence People’s Archive (SPPA) is a physical and digital collection of recorded memories and dreams commemorating the Black and Native American residents of the Public Street area – past and present. The archive includes cultural art, family photos, community print-works, digital scans, and audio recording that document the people, places, and ways of life that animate the neighborhoods surrounding Public Street. Learn more about the SPPA here.

Follow the PCL Instagram to see more from our Studio Visit series!