Artist Spotlight: Dana Heng & Moy Chuong | Public Street

This spring, Studio Loba sat down for a chat with Public Street artist team Dana Heng and Moy Chuong to learn more about their practice, their collaborations, and what they have in store for their PCL interventions. Read on to hear what they had to say.

Tell us a little about your practice.

Dana: My artistic practice is multidisciplinary and inspired by personal experiences, memories, wanting to connect to people… and wanting to learn how to make stuff, I guess? I’m also an educator and mentor at New Urban Arts, where I was also a student, and that space taught me about making artwork in an exploratory way, and in community with other people, and I think that has really impacted the way I do things now.

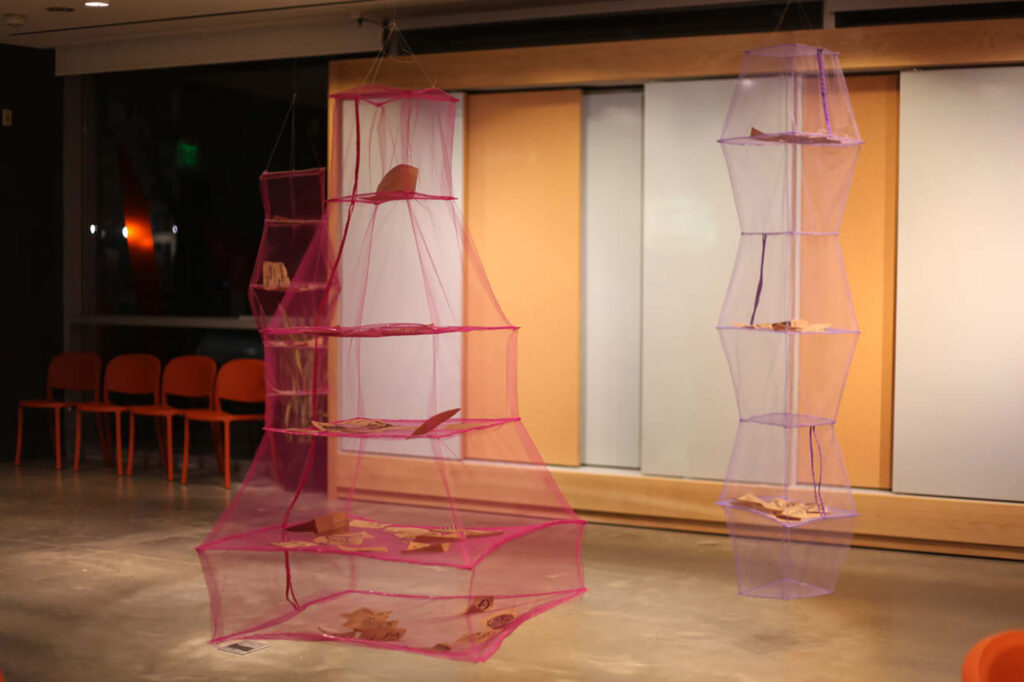

Moy: My artistic practice is largely focused on accessing a personal and family archive, and the idea of presenting that archive to the public. Similar to Dana, it’s a means of finding connection. As someone who comes from an immigrant family — I’m first-gen born in the US — there’s a lot of desire to access this culture that, for various reasons, different traumas have disrupted a connection to. I’m creating these works as a way to locate and build community. Most of my work is primarily focused on ceramics, but I also do fiber arts with ceramics, hand building and creating forms inspired by things I grew up with. A lot of it is translating plastic objects into ceramic objects — drawing on a cultural history to ceramics but also a contemporary cultural history to plastics manufacturing. A lot of plastic objects you find in grocery stores are ritual objects. They’re shrines created out of plastic, they’re dinnerware used as offerings… so I’m thinking a lot about the translation of those plastic objects.

What is your relationship with Public Street?

Moy: There’s a history of a Southeast Asian diaspora within South Providence and the Public Street area, and a lot of markets in the area serve those communities. So Dana and I both have this connection within our own cultural backgrounds, though Dana has a more personal relationship with it…

Dana: Yeah, at the end of Public Street that’s in the Elmwood neighborhood, there’s Apsara restaurant. And there’s a market — I don’t know who owns it now — which is where my parents’ store was. It was on this weird corner, the intersections are all kind of funky. (laughs) And in that block too, my mom had her tailor shop there. And then all the way at the other end of Public Street, before the waterfront, there’s the Wat — the Cambodian temple. So the whole street is bookended with these places that I have really prominent memories of. Also on Public & Broad Street, my family had a laundromat when I was a teenager. So I grew up kind of passively around Public Street, and before now, I wasn’t really intentionally thinking about the street itself. Like anyone, you’re just kind of there — it’s present, and maybe taken for granted. And I think that’s why we wanted to commemorate spaces that are everyday.

Moy: Yeah, we’re interested in the commemoration of things that, on first glance, don’t feel remarkable. The mundane things that form the fabric of the lives of people in South Providence — like going to the ethnic grocery store where all the foods have some personal or cultural significance, or going to the laundromat… We’re interested in the commemoration of these mundane things that speak to a larger idea of living and surviving in a country you’re not originally from.

We’re interested in the commemoration of things that, on first glance, don’t feel remarkable. The mundane things that form the fabric of the lives of people in South Providence… that speak to a larger idea of living and surviving in a country you’re not originally from.

Moy Chuong

Tell us where your PCL project is headed.

Moy: Right now, where our project lands is in thinking specifically about foodways. Dana and I both grew up in households where food was really important — gathering for family celebrations, cooking… Having that one aunty who makes sesame balls and everyone’s like, “This is the best one,” and she’ll never share her recipe, and then you try to make it and she doesn’t like it… (laughs) So I think we’re interested in celebrating those foodways. One way, formally, is thinking about groceries and the movement of produce. We’re taking visual inspiration from these produce boxes and turning them into planters. We’re also looking at various gardens that people have been tending to — backyard gardens where you’ll find lots of 5-gallon buckets, or a random piece of discarded metal that becomes a trellis…

Dana: We have resourceful gardening… (laughs) That’s what my grandma’s garden was like. The trellises were like tied-up broken brooms and any kind of sticks or stick-like things you could find …

What does commemoration mean to you?

Moy: I think part of it is shifting what is commemorated. A lot of public commemoration is that of histories that are already very dominant, well commemorated and well documented. And so we’re shifting towards things that feel everyday. Part of that is built into the work that we’re creating. We’re making these objects, these planters, that we hope don’t live in a gallery. We want them to end up in someone’s home, and become something they live with.

Dana: Yeah, and maybe down the line, that object is something that some kid sees in their life, and thinks, “That was like a funny little thing that I had growing up.” And maybe then they make their own art. (laughs) When you walk into certain Southeast Asian establishments, there’s usually a little altar on the floor, or hung up on the wall. And those are significant to me because they’re a mundane thing. You see it everywhere, and you have to make sure it’s clean and give an offering or light incense. It’s at once this everyday object, but also a sacred one. And I’d like to think about the pieces we make embodying that kind of spirit. Things that you see all the time, but are also special… and also not, you know? Things that are precious, but also not precious — they deserve commemoration.

It’s at once this everyday object, but also a sacred one. And I’d like to think about the pieces we make embodying that kind of spirit… Things that are precious, but also not precious — they deserve commemoration.

Dana Heng

Learn more about Dana and Moy here, and follow the PCL Instagram to see more from our Studio Visit series!